President's Message

Let us meet at the river…the James River that is.

The James River (named for King James I of England) is one of North America's most historic rivers; the first to be recorded by early English explorers. Along its shores, the first and second successful English settlements were established, those of Jamestown and Henricus, from which Henrico traces its origin.

For centuries prior to the English settlements, indigenous tribes of people occupied the area. From the falls of the James River where the City of Richmond (formerly Henrico territory) is today, the Powhatan Nation resided. Famously, Chief Powhatan's daughter Pocahontas married Englishman, John Rolfe, who successfully cultivated the cash crop of tobacco and the rest is our history. Along the James River, eight shires were created for jurisdictional purposes. Thirteen English Colonies were created beginning with the Colony off Virginia. Over time, three capitals would be established: Jamestown, Williamsburg and Richmond.

The success of the American Revolution for independence from England would be responsible for the creation of the United States of America. Much later, battlefields of a civil war that would divide the nation, took place along the same shores of the James.

This much abbreviated refresher of history leads us to our upcoming meeting on September 10, 2023. We are honored to

have Parker Agelasto, Executive Director of Capital Region Land Conservancy, speak with us about conservation efforts. As the only non-profit organization devoted specifically to the conservation of land within the capital region, CRLC continues its mission "to conserve and protect the natural and historic land and water resources of Virginia's Capital Region for the benefit of current and future generations." A number of those projects are located in Henrico's most historic areas, along the James River and Route 5.

What better way to appreciate conservation than to see it first-hand. Those of you who would like to join us at the Lilly Pad Restaurant for lunch at 1:00 before the meeting will enjoy a beautiful view of the James River, adjacent to Osborne Park. Please rsvp if you plan to join us for lunch in order to give a final count. We will convene for the quarterly meeting at 2:30 at Osborne Landing shelter #2. It is the first shelter on the right upon entering Osborne Park and Boat Landing. Visitors are always welcome. Read more about historic Osborne Landing at https://henrico.us/locations/osborne-landing/.

In the June newsletter a proposed change of HCHS By-laws was announced to allow terms of officers and directors

to begin in January of the calendar year which would require elections to be held in December. Other changes in

wordage to update the By-laws were recommended. The HCHS Executive Board approved all changes and a final vote of all membership will be taken at the September 10, 2023 meeting. The final document is available for review at www.henricohistoricalsociety.org/HCHSBylaws2023Final.pdf. A slate of nominees will be presented for elections to be held at the HCHS quarterly meeting December 3, 2023. We thank you for your continuing support. I look forward to see you at the Rivah!

Sarah Pace,

President

>Back to Top<

September Quarterly Meeting

Come join us for our third meeting of the year!

Date and Start Time:

- Sunday, September 10th at 2:30 PM

Location:

- Osborne Landing Shelter #2, 9530 Osborne Turnpike, Henrico, VA 23231

Guest Speaker:

- Parker Agelasto, Executive Director of the Capital Region Land Conservancy will speak about the organization's projects.

- Let's eat and meet! Before the meeting, let's get together for good food with good company right on the James River at the Lilly Pad Restaurant, which is located at 9680 Osborne Turnpike at Kingsland Marina.

We look forward to seeing you there!

>Back to Top<

In Memorium

The Henrico County Historical Society expresses its deepest sympathy to the families of:

- Ora Lee Pitts

- Arie Brandon

- Dana B. Hamel

>Back to Top<

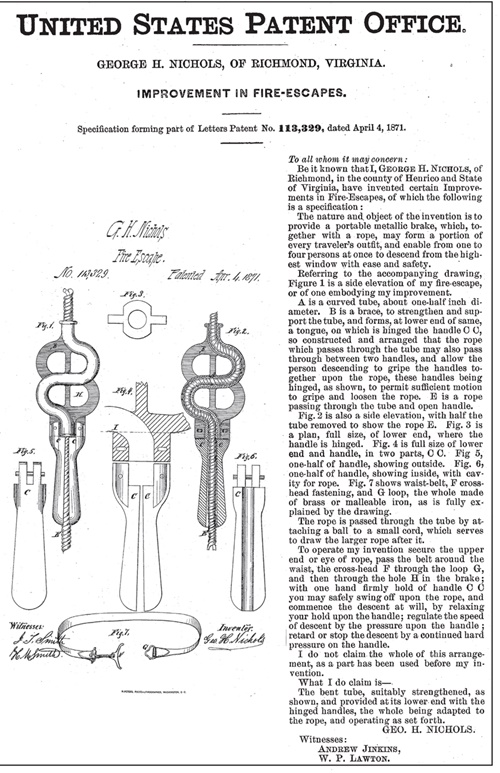

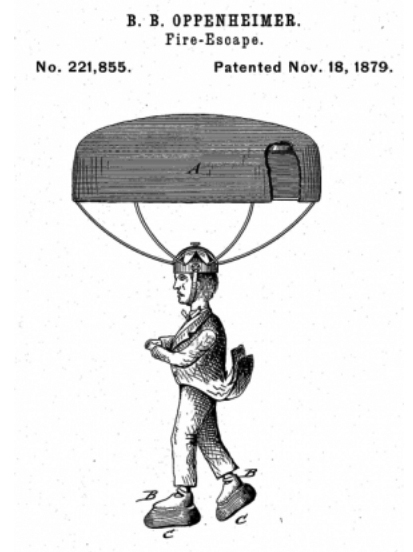

Inventive Henricoans

George H. Nichols' 1871 design for a personal fire escape was a clever solution to a potential nightmare for a hotel guest from a time when fire escape systems were not a normal feature of tall buildings. However, it is not as whimsical as Benjamin Oppenheimer's 1879 patent for a fire one that was a hat parachute.

>Back to Top<

Radiating Out of Richmond, the Mechanicsville Turnpike was Another . . . Spoke in the Wheel of Roads

I am apparently drawn to historic highways. For the forty plus years of my professional life as a public school teacher, I traveled a fair distance each day, and those daily commutes involved driving on what had been two of the nineteenth century's toll roads leading out of Richmond. For ten years, I took the Mechanicsville Turnpike to Stonewall Jackson Junior High School; and for the next thirty four years Osborne Turnpike was part of my commute to Varina High School. Little did I think I would later be drawn back to them as subjects for research and writing.

I wrote about Osborne Turnpike in March of this year, and now I invite you to revisit the Mechanicsville Turnpike with me. Established by an 1816 act of the General Assembly, it was one of eight Richmond area turnpikes incorporated between 1802 and 1818. Its seven sister roads included one connecting Manchester and Falling Creek (1802), the Richmond Turnpike running from the Deep Run Coal Pits to the Three Notched Road (1804); the Richmond and Columbia Turnpike (1804); Brook Turnpike (1816), Westham Turnpike (1816), Manchester and Petersburg Turnpike (1816) and the Richmond and Osborne Turnpike (1818).

The 1816 act authorized the directors to receive subscriptions to the amount of twenty thousand dollars or the establishment of "a turnpike road, from the of Richmond, crossing Chickahominy river between Meadow and New Bridges, until it intersects the Swamp road, on the north side of said river." The act called for the standard "width of sixty feet . . . with summer road for the use of horse and foot travellers." Summer roads were widened shoulders often used in dry, hot weather when ruts had been left in the main road. However, as the act noted, those requirements were "impracticable . . . as far as it respects the Chickahominy swamp, which must be causewayed and bridged." So an exception for that stretch of the road allowed "that it shall be sufficient for them to make such part of said road firm and permanent, and not less than twenty feet wide, and continue the same in good repair." The road connected with the City of Richmond at Eighteenth and Venable Streets, which posed a problem that the 1826 General Assembly addressed. Because there were "about one hundred yards where the said road enters into eighteenth street . . . which could not be made of that [sixty foot] width, in consequence of it being previously laid out and built upon," the company was allowed to let "that part of the road conform to the said eighteenth street continued."

Like other turnpikes in Virginia, the Richmond and Mechanicsville Turnpike would sell stock to fund the construction, and the State of Virginia would participate through the Internal Improvement Fund. For companies duly incorporated by the legislature, the fund would purchase up to two-fifths of the stock once twenty percent of the remaining three-fifths of the subscriptions had been bought and paid for. The Journal of the House of Delegates of Virginia for 1844-45 recounted the appropriations made for internal improvements between 1816 and 1844. It indicated that the state had originally appropriated twenty thousand dollars for both the Mechanicsville and Westham turnpikes in 1816 and fifty thousand for the Richmond and Osborne Turnpike in 1818.

Perhaps raising the remaining three-fifths of the funds was somewhat probmatic. The Richmond Enquirer of 20 September 1825 announced the 11 October public sale of stock on which money was still due to be held at a spot familiar, it seems, to other turnpike investors. It was at the Bell Tavern, the Main and 18th Street establishment where investors had first gathered to hatch the plan for the Brook Turnpike. Two years later the Richmond Enquirer of 14 August 1827 called for "Stockholders of the Mechanicsville Turnpike Company . . . to pay . . . Twenty Dollars on each Share, {additional subscription} held by them." The 1844 taxes paid on dividends recorded in the same report show that the Mechanicsville Turnpike Company had paid a total of $25.00 while the Brooke Turnpike paid $19.95. It appears that the two endeavors were comparatively successful, and by 1850 The Mechanicsville Turnpike Company paid $95.00 on dividends. However, it seems as if the road fell into disrepair. The General Assembly's 1861 re-enactment of the company's incorporation suggests some changes were underway, and the company apparently needed money. So the General Assembly authorized The Mechanicsville Turnpike Company to borrow up to $10,000.00 "for the purpose of repairing and improving their turnpike road."

And the company would change hands. The Richmond Dispatch of 25 June 1866 announced that day's auction sale of "all of the estate property, rights and franchises" of the Mechanicsville Turnpike Company at the toll gate. " Then the 7 July 1866 Daily Dispatch states, "A short time since an associat on of some of our most enterprising gentlemen bought out all the rights and franchises of the Mechanicsville Turnpike company with the intention of putting it in immediate and thorough repair"–likely a result of Civil War action. The article touted the beauty and history of the road, concluding that "our old friend Keesee, too, will be at the same old stand with his smiling face, and will receive the fractional currency necessary to pay the toll." J. B. Keesee was the toll keeper for the turnpike, but he apparently wasn't going to be part of the new directors' plans because the 3 August 1866 Daily Dispatch announced a 10:00 a.m. auction that day to sell "at theresidence of J. B. Keesee, Mechanicsville toll-gate, all of his household and kitchen furniture.

The New Mechanicsville Turnpike Company, as it was then called, remained in business and maintained the turnpike into the 1920s. But over those years, the attraction of turnpikes seems to have declined. Robert F. Hunter in "The Turnpike Movement in Virginia, 1816-1870" claims, "The main reason for the decline of turnpikes in Virginia and elsewhere was that they were inherently unsuited to profitable private enterprise . . . There existed side by side free public roads and private toll roads, of a quality that was in most cases indistinguishable. The public probably felt little remorse in by-passing the tollgates via the 'shunpikes.'"

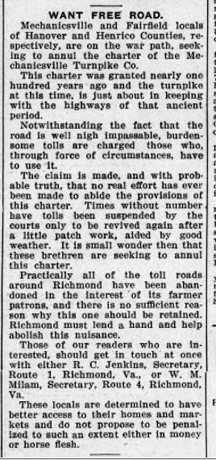

By the early twentieth century, dissatisfaction with toll roads, the Mechanicsville Turnpike in particular, grew as evidenced by the 21 September 1921 Richmond Times-Dispatch article headlined "Bar the Toll Gates." It complained that "Virginia has been a long time working out from under the toll-gate evil. It is not altogether free yet from that highway incubus. Here and there may be found the old-fashioned bar for the extraction of tolls. This is notably true of the Mechanicsville Turnpike on the outskirts of Richmond, but practically they have passed out of existence after serving a good purpose in the building and maintenance of decent roads when funds were not otherwise obtainable."

The death knell for the Mechanicsville Turnpike as a toll road was sounded when the 1920 General Assembly passed an act authorizing "the counties of Hanover, Henrico, King William, and the city of Richmond, or any one or more of them, to acquire by purchase or otherwise, or to contribute to the purchase of the . . . New Mechanicsville turnpike." Just how that acquisition came to pass is unclear; but thank goodness the road I travelled between 1974 and 1984 featured no toll gate.

Mechanicsville Turnpike Tolls

People, it seems, will collect almost anything; and for every collector there is quite likely an organization and/or a publication for like-minded collectors. For token collectors, formally known as vecturists, there is the publication titled The Fare Box. In the April 1968 issue, David E. Schenkman offered a brief article entitled "The Mechanicsville Turnpike Company of Virginia" in which he describes a poster he found that listed the rates of toll for the New Mechanicsville Turnpike Company, ranging from 3 cents "For a Horse, Mare, Mule or Gelding" to 50 cents "for a Wagon with four Horses, going and returning." A 13-cent toll like that pictured above was good "For a Cart with One Horse, going and returning," or "For a Cart with Two Horses, going and not returning." He also suggests that the tokens were probably used for a return toll when a round trip was purchased.

Turnpike Toll Houses Then and Now

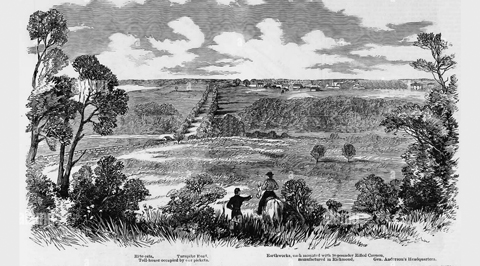

At the Chickahominy River

Just to the left of the beginning of the bridge is a cottage. The note at the bottom of the Civil War era drawing from Harper's Weekly identifies it as the "Toll-house occupied by our [Union] troops". The photograph below it shows the area from approximately the same vantage point today.

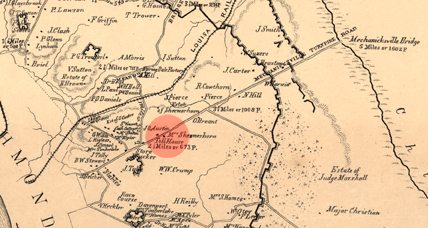

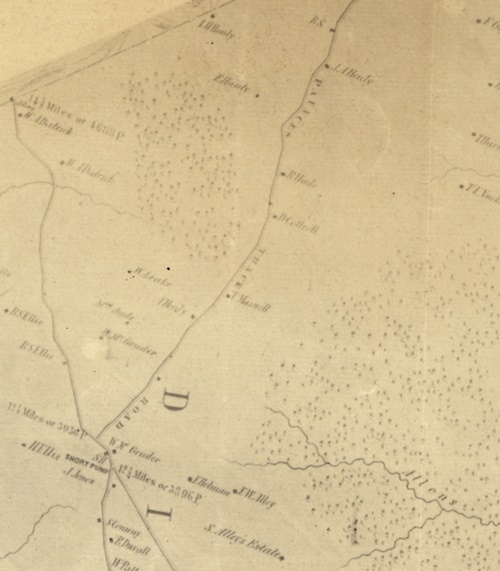

Coming Out of Richmond

Highlighted on the 1865 Smith Map of Henrico County is the toll house for the Mechanicsville Turnpike. The site today is occupied by the interchange with I-95 pictured below the map.

Beginning of the End

Articles like those in the 1915 Southern Planter gave voice to those dissatisfied with the conditions of the turnpike. It would only remain a toll road for a few more years.

And While We're Talking About Roads . . .

The Mechanicsville Turnpike changed over its two hundred plus year history, but its name remained the same. Other county road names have changed, evolved, or maybe just been misspelled. Whatever the case, the 27 March 1778 issue of the Virginia Gazette (below) advertised the sale of land in the county's west end "about fourteen miles above Richmond town." The announcement of sale is missing a slight detail in the road's name, but it appears to be something close to "Pensces Tract Road." (We welcome any help in deciphering it). Eighty years or so later, Smith's Map of the county identifies it as "Pances Tract Road." And today we call it Pouncey Tract Road.

Joey Boehling

>Back to Top<

Now You Know: Pounce Pot Set

Two couples pounced on the opportunity to identify the last issue's "What Do You Know?" object: Haywood and Mary Jo Wigglesworth and Ron and Nancy Grubbs. They identified the silver tray and shaker as a pounce pot set.

The pounce pot of this elegant set fit within the circular area on the tray and contained pounce, a fine ground powder made initially from either crushed bones of cuttlefish, pumice, a gum sandarac resin or even fine sand, leading them to sometimes be referred to as sanders, the contents being the consistency of sand. In the days before blotters and, obviously, ballpoint pens, a writer would gently shake the pounce over the surface of writing paper which had two functions, to smooth the rough surface of the paper to help the ink adhere and not bleed. It was also sprinkled over the ink to absorb any excess hence speeding up the drying time. The tray served as a receptacle of the pounce after it was brushed from the paper so that it could be poured back into the shaker.

The early nineteenth century saw the introduction of felt-bottomed wooden or metal blotters that could be rocked back and forth over the inked surface. By the middle of the 1800s, blotting paper had been developed; and for nearly a century, unless you used a pencil or didn't care about smudged or running ink, you needed a blotter. And because blotters were almost a basic necessity, the business world saw a great opportunity to advertise almost any product or service imaginable. And the artwork featured everything from pin-ups to Walt Disney characters, which he licensed for that purpose.

The 1940s saw the introduction of ball-point pens and the demise of blotters. Perhaps, the increasingly fast pace of daily life de-emphasized the care and attention to writing that was once required.

Writing Amenities

When guests in nineteenth and early twentieth century Richmond hotels took advantage of the hotel's stationery and pens, they needed a blotter like that seen above. The guest at Ford's Hotel apparently didn't have access to one as the "Dear" in the salutation indicates.

>Back to Top<

What Do You Know?

This wooden object's base is 39" long. At its widest point it is 7" wide tapering to a width of 4". It is 15" tall at the highest point, and the square container in the middle is 5" square. A small metal spout comes out at its bottom."

Email your answers to jboehling@verizon.net.

We look forward to hearing from you.

>Back to Top<

News 2023: Third Quarter

First Quarter | Second Quarter | Fourth Quarter

Home | Henrico | Maps | Genealogy | Preservation | Membership | Shopping | HCHS

|