President's Message

In conversation recently someone related how she had grown up in a rural community without the modern conveniences we have today. At the age of six while the family sat on the front porch, her 21 year old brother was struck and killed by lightning as he walked around the side of their home. Her mother gave instructions to ring the dinner bell. Ringing the bell at any other time of the day was a distress call and within in minutes neighbors came from as far away as the signal could be heard. The thought of this family's tragedy and how neighbors came to assist one another brought tears to my eyes.

As children, we loved hearing the many stories told by our PaPa Harris of living on a farm in Louisa County.

Growing up in suburban Henrico County (which had previously been a rural community of farmland) I never heard mention of the distress call of the dinner bell. Not much first-hand recall is available online relating to the dinner bell but the following information was found at www.mywilson.homestead.com.

The dinner bell is just one more thing that served its purpose then disappeared, as did coal-oil lamps and chamber pots, leaving only memories.

One of the many things that I looked forward to, in the summer, was going to Frances, Kentucky to visit Grandma and Grandpa Whitt's farm and getting to ring the dinner bell at 11:30 on weekdays. When I was a child almost every farm had a dinner bell, it was used to call the men to the house when the noon meal, dinner as they called it, was ready. Dinner would be ready at 12:00 o'clock noon, but a half hour was allowed to bring the team of mules, Kate and Jude, to the barn to be fed and for Grandpa and the hired hands to get washed up.

When Kate and Jude heard the first peal of the dinner bell, they knew it was time to eat and rest so they stopped dead in their tracks. If they were stopped in the middle of a row, Grandpa had to prod them on to the end of the row so they could be unhitched from the plow or whatever they were pulling. After the meal, the men went outside and sat on the porch, or under a shade tree to rest for about an hour, by that time Kate and Jude were rested too and then back to the field to work until sundown.

In those days watches were hard to come by and not all men had one. The old clock, on the wall or on the mantelpiece, was the only means of telling time. The clock in the Whitt house, sat on the mantelpiece above a big open fireplace in Grandma and Grandpa's bedroom, which in the winter was also their sitting room. They referred to that room as "the house", if we were in the kitchen grandma would tell me to go in "the house" and see what time it was. The reason for calling it the house was, when they were young, kitchens were built apart from the main house to protect it from fire and to keep from heating the whole house in the summer. Grandma checked the time often, as she wanted to have the meal ready at the exact same time every day.

In those days when a farmer was in the field he could guess the time of day, if the sun was shining, within an hour of noon. As he had been working since daylight he sometimes used this method to see how much longer it would be until dinner. He would stand with his back toward the sun, with its rays shining over his left shoulder. He put his right foot out as if to take a normal step. The position of the toe of his brogan and the shadow of his head gave him an approximate time. Of course this method didn't work on cloudy days.

Before Grandpa's mother, Sarah, died she told Grandpa and his sister Martha, that one of them could have her horse and the other could have a pocket watch, her most prized possessions. Aunt Martha chose the horse so Grandpa got the watch. it was a beautiful gold watch, much larger than the pocket watches of today. The face had a solid cover with an engraved design on it. When he wanted to see what time it was, he pressed a small button, which opened the cover. After he checked the time the cover was snapped shut, He could wind it either by the stem or with a small key.

Grandpa carried his watch, which was on a chain, in his vest pocket, on the other end of the chain was a beautiful, multi-faceted, crystal watch fob. The chain hung down from the watch, looped back up through one of the buttonholes and the fob dangled down on the front of his vest. All of the grandhcildren and great grandhhildren were fascinated with the glistening watch fob. He carried his watch only on Saturday and Sunday or on rare occasions when they went visiting. To avoid abusing his watch he didn't dare carry it to work in the fields, so the dinner bell served as his timepiece.

The dinner bell could be heard for a distance of up to one mile. We were forbidden to ring the dinner bell except at noon, if it was rung at any other time it was a distress signal, if there was an accident, fire, sickness, or other emergency, the dinner bell was rung to call for help. Everyone within hearing distance would drop everything and run to give aid in an emergency.

When visiting in Kentucky, I always drive up the gravel road to the Whitt farm on top of Bald Knob. I drive down a lane and stop in front of the remains of the old ice house. If I close my eyes for a moment and listen, I can still hear the peals of the old dinner bell.

When Grandpa Whitt died, August 10th 1935, the pocket watch was passed on to his son, Allie Louis. It was then given to Allie Louis Whitt Jr. (Dick). When the watch is mentioned, Dick always makes a remark that Grandpa was a lot smarter than Aunt Martha. Today, the watch is proudly displayed under a glass dome in his home, but Aunt Martha's horse has been long gone.

Mildred Y. Wilson 9-4-1998

Our own efforts to build a replica kitchen for Meadow Farm Living History Museum will help preserve the history of farming in Henrico County in the mid 1800s. The latest fundraising event will be "Walkerton Amusement Garden" to be held on Sat. September 24th. This event will replicate what was the forerunner of the amuesement parks we have today. From the late 1600s to the mid 1800s at a time when there were very strict social restrictions, people of all levels of society, from nobility to the common people of the streets, enjoyed entertainment while strolling in the gardens outside of London. There were also gardens in America, two of which were located in Richmond, Virginia, one in 1802 and the other in 1805. We have put together an amazing program of entertainment and refreshment that were enjoyed in that era for you to experience. It is very heartwarming that this event is a conmunity effort with all of the entertainment performed by volunteers. Just as the community would respond to the distress call of the dinner bell, our community has responded to the call for this project. We hope you will attend. If you cannot attend, donations will be greatly appreciated and may be addressed to HCHS Kitchen Project and mailed to PO Box 90775, Henrico Virginia 23273. The Henrico County Historical Society is a 501(c)3 charitable organization. Donations are tax deductible as admissible by State and Federal law.We thank you for your support of this community effort.

Sarah Pace, President

Our December meeting at the Virginia War Memorial will commemorate the 75th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, not the 50th.

>Back to Top<

September Quarterly Meeting

Sunday, September 11, 2016 starting at 2:30 p.m. Board meeting starts at 1:30 p.m.

Virginia Randolph Education Center Auditorium, located at 22016 Mountain Road in Glen Allen, VA 23060.

Ann Lawson, chairperson of the Mount Olive Historical Ministry will give a presentation on the history of Mount Olive Baptist Church. A tour will also be given of The Virginia Randolph Museum.

>Back to Top<

Walkerton Amusement Garden

Walkerton Tavern

2892 Mountain Road

Glen Allen, VA 23060

Saturday, September 24, 4-7 p.m.

Rain Date: Sunday, September 25

Cost: $20 per person.

Long before there was Kings Dominion or Busch Gardens, Londoners enjoyed their own type of amusement park: the Pleasure Garden - a place for an evening of outdoor entertainment with manicured walks and fountains, refreshments, concerts, and exotic street entertainers.

Join the Friends of Meadow Farm and the Henrico County Historical Society for a journey back in time when we recreate an experience that novelist Tobias Smollett made him think he "was in some enchanted castle or fairy palace." You'll be thoroughly entertained and help raise funds to construct a period kitchen at the Meadow Farm Living History Museum.

Tickets may be purchased online via our shopping page to include a PayPal processing fee or by using this mail-in form.

>Back to Top<

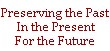

Minister from Deep Run and North Run Baptist Churches Commemorated

Rev. Henry Satterwhite (1816-1877), seen at the right, ministered to Deep Run Baptist Church and North Run Baptist Church in Henrico County. Listed as a messenger at Deep Run in 1846, he left and became one of the six founders of Berea Baptist Church in Hanover County. He returned to Deep Run as pastor from 1867 to 1877. He is buried at Berea; and on July 2, 2016, descendants and famly members, including longtime Henrico resident Dot Chewning (right) attended the placement of a new ledger compementing the old, nearly illegible gravestone marking his final resting place.

>Back to Top<

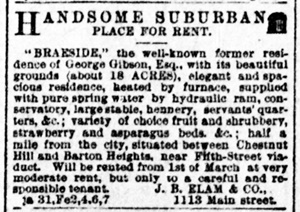

A Window on Nineteenth Century Life Through the Daily Record at Braeside

History is not always a story told in a straight line, nor is it the story solely of "larger than life" figures. It can follow indirect paths through documents left behind by fairly obscure people, and the paths these documents help to chart make the past more personal, more approachable, more interconnected and often more interesting.

Diaries and journals can do this, and regular readers of these pages will be familiar with the musings and observations of various women of nineteenth century Henrico. Past issues have presented Mary C. Powell's plantation journal and its detail about farm life, Mary Mason Tabb Hubard's account of her artist husband's efforts at casting cannons for the Confederate army and his fatal accident at the foundry, and, most recently, Emma Mordecai's notes penned during her time at Rosewood.

In fact, the interconnectedness of the past is illustrated in yet another diary from the time - that of Ann Elizabeth Gibson, who on Tuesday, May 24, 1874, noted that she "Received from Emma Mordecai a most rare & beautiful floral present - a blue jessamine & c." However, unlike the records left by Mordecai and the others, the jottings of Mrs. Gibson, actually called Bessie, are brief - an almost endless string of daily weather reports and names of visitors, always concluding, curiously, with the number of eggs gathered that day.

Bessie Gibson, born Ann Elizabeth Gibson, was first married to Rev. Hobart M. Bartlett, and lived in North Carolina. George Gibson, her cousin, was her second husband. He was a partner in Spotts & Gibson, a commercial grocery in Richmond, and the couple lived at Braeside on about eighteen acres a half-mile outside the city on Meadowbridge Road.

Perhaps, the format of the book with its very limited space for each day's entry, accounts for the brevity of those recordings, for they are not as expansive or reflective as the Powell, Hubard, or Mordecai accounts. However, there is an entry for every day of 1874, and some of them can lead us down narrow little paths to practices and products that illustrate aspects of daily life in the third quarter of the nineteen century. This issue will follow some of these paths.

Ann Elizabeth Gibson's diary is included in the Chamberlayne family papers housed at the Virginia Historical Society.

Joey Boehling

Buried at Hollywood. The graves of George Gibson (1820-1896) and his wife Bessie (1817-1897) lie in a shaded plot with a view of the James River at Hollywood Cemetery.

>Back to Top<

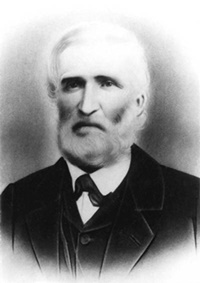

Medicine: Bitter Water Cure

On Thursday, August 13, George Gibson fell ill, and his condition caused Bessie great concern for almost a week. The entries give us an indication of the degree of attention paid by doctors and example of a patent cure of the time. She wrote:

George came home sick in the middle of the day. 3 eggs.

The next day she records the following:

...My George was sick in bed - afraid he is going to have a serious illness - don't at all like his symptoms...I think I cannot do anything but wait on George. 3 eggs.

George's condition stayed the same on Saturday, when Bessie wrote:

George no better - has taken a good deal of strong medicine without any effect. I feel very uneasy. 4 eggs.

On Sunday, we find that:

Finally about four o'clock this afternoon there was universal rejoicing [it isn't clear why, but there must have been some improvement]. 3 eggs.

And Monday, August 17 brought some improvement, with the physician making a double house call:

George is certainly better but very far from being 'all right' now. The Doctor was here twice yesterday - came this morning and paid a nice long visit. I am so sleepy from the broken rest for the last three nights that I can barely keep my eyes open to write. 3 eggs.

But the improvement was short lived, and Bessie chose an interestingly euphemistic way of describing the illness:

George's condition still keeps me very uneasy. Stomach and bowels seem to have forgotten how to do their work and I cannot help apprehending all sorts of ailments - have such wretched nights. 1 egg.

Wednesday 19 finally brought relief and mention of the treatment that finally worked:

Thank a kind Providence. George seems to be decidely better. The bitter water has acted well and seems to be setting things straight. The Doctor took his professional leave this morning...10 eggs.

So it seems that bitter water was what brought relief to George. In Von Ziemssen's Handbook of General Therapeutics (1885), Otto Leichtenstern wrote that bitter waters "always contain, besides their constituent, sulphate of magnesia, a large suppy of sulphate of soda...Their chief action, especially in a therapeutic point of view is their purgative one." He went on to describe medical experiences done on a seemlingly popular brand of the water, Friedrichshall; and this was available in Richmond as the advertisement from the Richmond Dispatch of 5 April 1873 illustrates.

On a lighter note, it is interesting to note the number of eggs that Mrs. Gibson collected each day of George's illness and speculate upon the possible effect of family distress on daily egg production.

>Back to Top<

Flooring Treatment: Flooring It

A number of entries in Elizabeth Gibson's diary complain about the carpenters disturbing her when they did work at Braeside. But once they had finished, she had some interior decorating to tend to. On Wednesday, September 9, she wrote:

Went to town this afternooon - chose piece of oil cloth for stair case & carpet for one of the rooms...0 eggs.

Oilcloth production: Workers pose in an early oilcloth manufacturing plant. Photo from Hubbard Free Library Collection.

The following day she assessed her efforts and did some preserving:

The oil cloth put down looks very pretty - almost done fixing. Over handled pickles - in a miserable condition - lost all their acid...15 eggs.

Her choice of oilcloth for the stairs was a fairly common technique of the day. It was an inexpensive floor covering produced by streching linen or heavy cotton and coating it with a sizing solution. Finally the cloth was coated with a mixture of linseed oil and paint pigment. Its expense is illustrated in the ad below taken from the Richmond Dispatch of 29 May 1872. Locally, a fine example of it can be found on the floor of the entry hall in the White House of the Confederacy.

>Back to Top<

Visiting: Making One's Presence Known

A lady paying a social visit in the nineteenth century would arrive bearing a calling card to announce her arrival. It would announce her to the servants or would be left to indicate that she had attempted a visit. Such cards would be left on a fancy tray like the one in the accompanying photograph. Mrs. Gibson must have had a most unusual collection of these items for she wrote on Wednesday, October 14, "Went to town this afternoon to do some shopping & leave some visiting cards in the shape of egg plants. 0 eggs."

Or perhaps, she had actually left vegetables as gifts and was playfully referring to them. At any rate, she was performing a standard social ritual of the time.

And her choice of time corresponded to expectations of the time. According to the website, www.americanstatonary.com, "Visiting or calling hours were limited, and most sensibly, to a restricted time in the afternoon. No one not privileged on pressing business, or extremely intimate would think of invading a household before three o'clock."

And there were messages sent by those who left a calling card when they folded a corner.

Turning the right hand upper corner indicated a visit in person (as opposed to being sent by a servant). Folding the left hand upper corner indicated a congratulatory visit. A condolence visit could be indicated by folding the left hand lower corner. And taking leave on a long trip could be announced with a fold of the right hand lower corner.

>Back to Top<

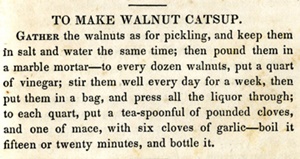

Culinary Arts: Sauced

In the entry for Thursday, August 25, Bessie Gibson said that she had "Made some walnut catsup...3 eggs"

This condiment was apparently of English derivation and was somewhat similar to today's steak sauce. In The Virginia House Wife (1846), Mary Randolph offered the recipe shown here.

>Back to Top<

Conclusion (almost)

On Thursday, December 31, 1874, Elizabeth completed her diary, writing: "...the last night of the year - what a record pf trifles and wasted time. 'Enter not into judgment with thy servant, O Lord.' 2 eggs."

We disagree. Those "trifles and wasted time" led us down some lovely paths and also caused us to veer into several other related records investigated on the following page. We thank her for her subtle guidance.

By the way, she collected 1,851 eggs in 1874.

>Back to Top<

Other Paths

Not only did Bessie Gibson's diary lead us to the investigation of small details of nineteenth century life, but it also led to several other related documents that cast more intimate and detailed light on her life - a commonplace book she kept, a deed, tax records, the special agricultural census and a few newpaper advertisements.

>Back to Top<

Lingering Pain: Recording Her Grief

While some documents can tell us about the times, others can connect us to timeless human conditions - and some of those will break your heart. So it is with Mrs. Gibson's 80-page commonplace book that she apparently kept from 1862 to 1891.

It is devoted to her son, George Haxall Gibson, who died at the age of four; and it contains poems, hymns, essays and meditations, most copied but some probably original, all centering on the death of a child.

It opens with the transcription of the hymn "There stands our child before the Lord" and contains many other peoms including "A Shadow & A Sunbeam" and "To My Boy in Heaven."

And it is more than a mere compilation of the works of others. At one point, she copies, "Those Footsteps," a poem by Alexander Anderson. Its first four lines read as follows:

In the quiet hush of the tender night

When my eyes fill up

with tears,

Comes my darling

unto me, all golden

bright

With the sunshine of

three sweet years.

However Mrs. Gibson takes the fourth line and changes a single word. Each time she picks up the book, it seems the world is immediately viewed through the lens of her loss; and in her version, three becomes four.

But the most moving entry in the booklet is on the twenty-seventh page, she wrote, "Little George - Entered into Life Thursday Oct 9th 1862 - 11 1/2 a.m."

It is followed by a possibly original poem "Affectionately dedicated to his earthly Father" introduced with a reference to John 4:50: "Go thy way - thy son liveth." Here is the verse:

Yes! weeping Father! Go thy way

In faith - in hope - in joy -

For kinder - stronger arms than thine

Surround thy blessed boy!

And though a "little while" removed

From thy fonding aching sight -

He views his Heavenly Father's face

In worlds of cloudless light!

And there he lives - untouched by sin

Or sorrow - want - or care -

And waits to greet the loved of earth

His heavenly lot to share.

Then let us press our pilgrim feet

Towards that eternal shore -

Where every faithful child of God

Shall live- to die no more!

George Haxall:

Only son of GEORGE & BESSIE GIBSON

Born Aug 16th 1858

Died Oct 9th 1862

Hollywood Cemetery

>Back to Top<

Owning & Farming

Braieside. This ad from the Richmond Dispatch (January 31, 1892) describes the property ad improvements. George and Bessie had passed away, but the property was still identified with the family.

The deed of October 15, 1868, for at least part of Braeside's land offers us an insight into women's property rights in nineteenth century Virginia. It names "George Gibson Trustee for A. E. J. Gibson his wife." It states that "George Gibson Trustee shall hold the said lands for the sole and separate of his wife the said A. E. J. Gibson free from the control of debts and liabilities of her present husband or any husband she may hereafter take, just as if she were a single woman."

Her $2050 bought the land, but she did not technically own it. She bought the land nine years too early; for in 1877 the Code of Virginia was changed to read, "A married woman shall have the right to acquire, hold, use, control and dispose of property as if she were unmarried and such power of use, control and disposition shall apply to all property of a married woman which has been acquired by her since April 4 1877, or shall be hereafter acquired."

Even after 1877, the trust remained in effect, and property tax records for 1880 are listed under George's name as trustee for A. E. J. Gibson. The record shows the land assessed at $200 per acre with a total value of land and buildings of $2575.

Consulting the 1870 and 1880 agricultural censuses shows us the 16-acre farm grew to 20 acres in 1880 and increased in total value from $5000 to $10,000. The 1870 record indicates the following yields: 40 bushels of rye, 40 of Indian corn, 25 of oats, 10 of potatoes, 25 of sweet potatoes and 50 pounds of butter. Total value of agricultural production was listed as $1500 for both 1870 and 1880.

By 1880, the farm was more valuable ($10,000) but, it seems, less active, requiring an outlay of only $325 in wages for labor compared to the $1000 spent in 1870. The farm produced 25 tons of hay in 1880, and its 40 poultry units produced 100 dozen eggs.

>Back to Top<

Now You Know: Fluting Iron Eased the Creation of a New Wrinkle in Fashion

Congratulations to Jo Garey and Leiss van der Linden-Brusse (second consecutive correct identification) for recognizing the implement at the right as a device for ironing ruffles on dresses.

It's actually from Bessie Gibson's time, because in the 1870s dressmakers were using pleated frills, also called fluting, lavishly. Ironing this fluting was difficult and meant that there was plenty of use for a fluting machine.

Obviously, the iron had to be hot. To heat the ridged rollers that pressed the fluting, a heated stick, called a heating iron, went into the hollow interior of each roller through openings on the handle end. The clamp held the device in place while the dress was drawn through the iron. The illustration from Godey's Lady's Book magazine for August 1870 shows dresses with fancy pleated frills.

>Back to Top<

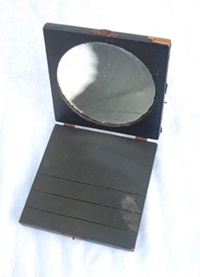

What Do You Know?

Each side of the hinged object pictured here is 6" square and 1/2" thick. The top has a 5" concave mirror, and there are three narrow grooves in the bottom.

Do you know what it is?

Email your answers to jboehling@verizon.net.

>Back to Top<

News 2016: Third Quarter

First Quarter | Second Quarter | Fourth Quarter

Home | Henrico | Maps | Genealogy | Preservation | Membership | Shopping | HCHS

|