President's Message

I wrote not too long ago about organizing files and coming across all sorts of HCHS history of people, places, and other things. Recently, in the process of gathering information for fundraising purposes to build a replica mid-1800s kitchen at Meadow Farm, I came across photos of all the events we sponsored with the help of HCHS volunteers and volunteers from a number of organizations. There were the Tea Dances at Walkerton Tavern with the Colonial Dance Club of Richmond and the Twelfth Night dances with the 12th Virginia living history reenactors. We held the Walkerton Amusement Garden event that included Chief Terry Price of the Wolf Creek Cherokee Tribe, violinists, a ventriloquist, a magician, a mystery theater director and the Henrico Concert Band. And most recently the Friends of Meadow Farm volunteered their time and donations for a benefit yard sale for the "Kitchen" at the Glen Allen Market. They came from all over the region to participate in these events: Northern Virginia, Spotsylvania County, Mathews, Chesterfield County, Hanover County and Louisa County. Presentations have been made to a number of local civic organizations. It has been a wonderful community outreach project, and I am overwhelmed with gratitude of those who freely gave their time and talent.

Meadow Farm is a special place. Located at 3400 Mountain Road, Glen Allen, VA 23060 in Crump Park, the farm and its inhabitants have seen much of American history. Originally an Indian Trail, historic Mountain Road was much traveled during the Colonia era. During the Revolutionary War Lafayette passed over this road on his way to Yorktown. It was from Meadow Farm that Tom and Pharoah (Sheppard family slaves) warned of a slave uprising which became known as Gabriel's Rebellion. During the War Between the States, Major General Phillip Sheridan led his army down Mountain Road en route to what would become known as the Battle of Yellow Tavern. It is said Major General George Armstrong Custer tied his horse to a cedar tree in front of the farmhouse.

The history of Meadow Farm is well documented. The Sheppard family kept meticulous records through seven generations that lived there.

Meadow Farm is today a living history museum, depicting life on a farm in the mid-1800s. It has long been a dream of the Henrico County Historical Society and Friends of Meadow Farm to build a kitchen that would be central to telling the amazing story of Meadow Farm.

Farming has been a part of Henrico history since its origin in 1611. Until the rapid expansion of the 1950s and the development of suburban neighborhoods, much of Henrico was farmland. Interestingly, there are still pastures with cows located in Pinedale Farms and off Nuckols Road, owned by a family that has remained living on Three Chopt Road for a number of generations.

School children visit Meadow Farm, some of whom have never seen farm animals or vegetables outside of the grocery store. It is part of the education we hope to promote, and the kitchen will contribute, not only for the children of today but also as a legacy we leave to future generations.

Wonderful progress has recently been made in our efforts. Raplph Higgins, a local artist, has created a watercolor rendering of the farmhouse with the kitchen building. It is said a picture is worth a thousand words. It brings the concept of the kitchen to life. It can be viewed at the Orientation Center at the "Farm."

Our recent efforts have involved applying for grants, many of which have matching fund requirements. Won't you please consider making a donation to assist with reaching those goals? No donation is too small or too large.

It could be your donation that makes our dream come true and builds the kitchen.

Please make donations payable to HCHS with Meadow Farm Kitchen in the notation and mail to P.O. Box 9775, Henrico, VA 23273. We thank you.

Sarah Pace,

President

>Back to Top<

Cooking Up Plans for Meadow Farm

Julian Charity, new site manager for Meadow Farm Museum, stands at the original site of the farm's kitchen building marked by an outline of bricks. It is also his preferred site for a reconstructed kitchen building for which funds are currently being raised.

The Henrico County Historical Society, as the President's Message states, is most anxious to aid in the fundraising, and our HCHS Project Manager, John Hoogakker can tell you all about it.

For additional information, please contact John at (804)-418-1630 or jhoogakker@wlu.edu.

>Back to Top<

September Quarterly Meeting

Our September Quarterly Meeting will be Sunday, September 8th, starting 2:30, at the Libbie Mill Library. The library is located at 2100 Libble Lake E St. in Richmond, VA.

Join us to hear John Hoogakker speak about the history of the University of Richmond and its campus, which lies partially in Henrico County and was named by the Princeton Review as America's most beautiful campus in 2000.

>Back to Top<

Join Us on APHA Field Trip

Plan on joining us in the fun on a field trip with the Association for the Preservation of Henrico Antiquities to

James Monroe's Birthplace and George Washington's Birthplace!

We will be carpooling from Dabbs House at 9:00 am on Saturday, October 26th. For information, please contact Sarah Pace at (804) 839-2407 or sarah.pace@va.metrocast.net, or check out Shopping page on Henrico County Historical Society's website.

>Back to Top<

In Memorium

The Henrico County Historical Society extends it deepest sympathy to the family of Emily Branch Ragsdale Nuckols, who passed away on 6 June 2019.

We also express our deepest sympathy to the family of Karenne Wood, an advocate for Virginia Indians and speaker at our June 2018 meeting. She passed away 21 July 2019.

>Back to Top<

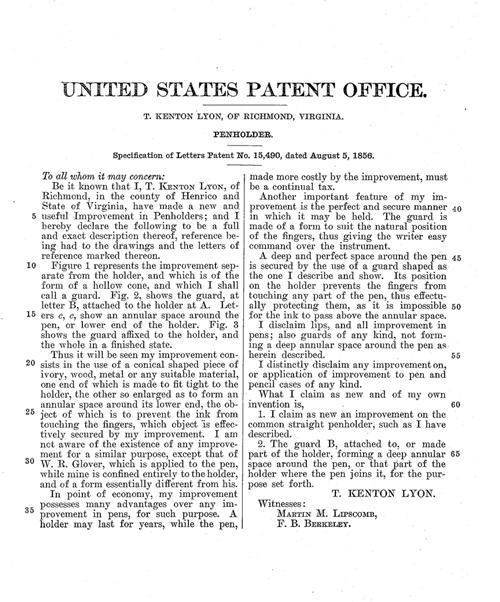

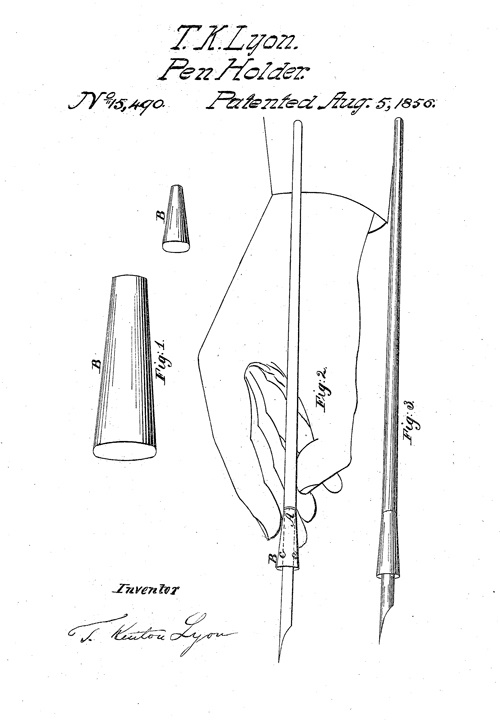

Inventive Henricoans

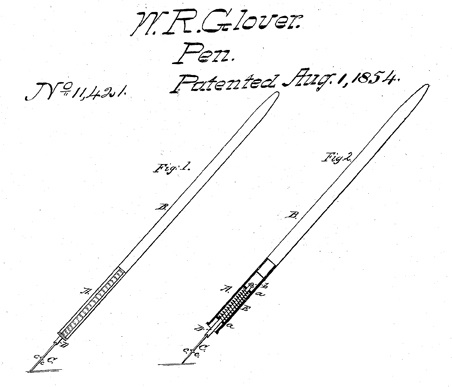

It seems as if nothing is too simple to earn a patent. Such seems to be the case with T. Kenton Ryan's pen holder, or as he calls it in his explanation, a "guard." His suggested materials ranged from upsale ivory to economical wood, all used to keep the writer's fingers from being stained by ink. Ryan even made a nod toward ergonomic efficiency by noting that "The guard is made of a form to suit the natural form of the fingers.

Ryan alludes to W.R. Glover's more complicated invention whose goal was also to keep the hands clean. However, his invention seemed a bit like a modern ball-point pen because he mounted the nib on a spring to make the pen move more smoothly on the writing surface.

>Back to Top<

Ropewalks: An Industrial Disappearing Act

Although iceboxes, typewriters, and wood cook stoves have given way to refrigerators, word processors and microwave ovens, they remain familiar to most of us. But as the march of technology has progressed, many other early developments have become obscure - some even unrecognizable to the general population. How many people are familiar with an Edison wax cylinder recording, the first step on the way to today's digitized music? Or a magic lantern, an early kerosene-lamp powered projector, the forerunner of today's home entertainment devices? Mention those to most people, and you'll often be met with a blank store or a furrowed brow - the same expression that would probably be elicited by the mention of a ropewalk, a much needed eighteenth and nineteenth century rope-making facility. And although those rope-making operations could be found in Henrico County and Richmond, few references to or reminders of them can any longer be found in the area or in the local memory. But before we try to refresh that local memory of Henrico's ropewalks, it would be good to consider the fibers that the ropewalks used.

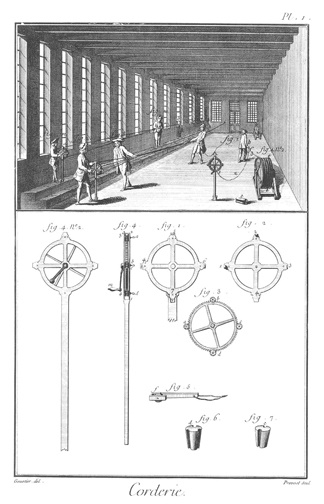

The image above shows an etching and a diagram. The etching depicts an eighteenth century ropewalk in the process of making cordage. The diagram shows a spinning wheel with four "whirls." Two "tops" are also shown.

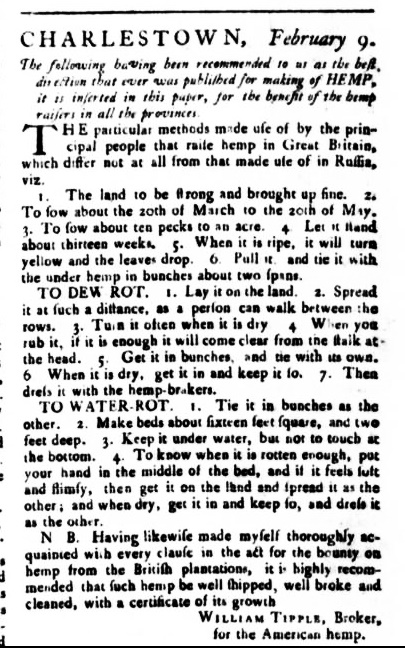

The hemp plant provided the fibers for the rope that was integral to early naval and shipping operations. And a great deal of it was needed. For example, according to the USS Constitution Museum, a ship the size of the eighteenth-century "Old Ironsides" would require approximately 40 miles of rope for its rigging, and the rope required for the ship's 1927 restoration weighed 67 tons. In "Hemp in Colonial Virginia," G. Melvin Baird indicates that six tons of rotted hemp would yield about a ton of fiber, and that fiber needed further refining. So the English navy's need was great, and that explains the Virginia Assembly's 1632 order "that every planter as soone as he may, provide seede of flaxe and hempe and sowe the same." And to encourage the cultivation of hemp, the 9 April 1767 Virginia Gazette ran an advertisement giving instructions for the raising of hemp.

After preparing the ground, growing hemp did not require a great deal of attention since its resin prevented attack by insects. The stalks, ten feet tall or higher, could be harvested from late July through October, tied in sheaves and set out to dry. Then they were ready to be rotted (or retted) by soaking them to dissolve the plant's resinous gum and free the fiber from the bark. Ater drying the rotted stalks, they were fed through a break. Stalks were placed between the jaws of the break and the top blade was brought down on them, repeating the breaking as the stalks were pulled through. The broken bits fell to the ground, and the remaining fibers were whipped against the side of the break to remove the rest.

Hemp break. In the image above, this five-foot long instrument broke rotted and dried hemp fibers to free the fibers.

At this point the hemp was ready to go to a manufacturer, and this was the raw material that Henrico's ropewalks converted into usable cordage. Some of it went to factory at Four Mile Creek for weaving into sail duck. In "A War-Inspired Industry," G. Melvin Herdon cited a 10 November 1777 memorandum from Sampson Mathews (Virginia State Auditors, Item No. 218) noting that George Bright's wagon was loaded at Staunton with "4 Bales of Hemp and 6 Spinning Wheels for the Linen Factory at 4 Mile Creek."

But whether the hemp was for sail duck or headed to a ropewalk, workers in those facilities needed to perform two more steps to refine it: scutching and heckling. Scutching removed the last of the detritus from the fibers by repeatedly pulling handfuls of fiber through a semi-circular opening on top of a board while striking it with a two-sided wooded scutching knife until the fiber was completely clean and the fibers were straight and even. Heckling was a fine skill and involved pulling the fibers through a heckle, a board with sharp vertical spikes that separated the fibers into individual filaments, got rid of short fibers (tow) and equalized and rendered the filaments parallel.

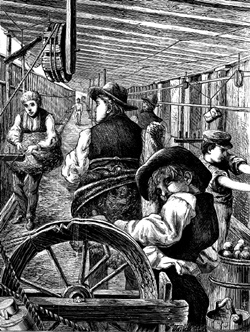

Those clean, parallel filaments were not ready for the ropemaking process, the first step of which accounted for the rather curious term ropewalk. A worker called a spinner rapped a bundle of heckled hemp around his waist and attached a number of filaments to a "whirl," a small spindle. Another worker turned a large wheel which powered up to six "whirls" for up to six spinners. As the wheel turned the spindle, the spinner slowly walked backwards while he led filaments onto the developing yarn until he reached the end of the walk or the desired length of the yarn. It could be a long walk since some ropewalks were up to a quarter of a mile long; and to keep the yarn from tangling or knotting, he hung it from pegs along the way. Then it was wound on a reel.

Spinner at work. In the picture left, with hemp fibers bundled around his waist, the spinner walks backwards to form yarn.

The yarn would then be turned into strands, but if the rope was to be for marine use, it was run through a vessel of melted tar and then through a small hole to squeeze out the excess and would on another reel. Depending on the size of the strand desired, the ends of three or more yarns were attached to the "whirls," while the other end was attached to a swivel hook at the other end of the walk. Turning the wheel in the opposite direction from the twist on the yarn produced a strand.

The opposite direction of the twist would prevent unraveling, so the final twist to make the rope was done by twisting three or more strands together in the opposite direction again. This step was called "laying" the rope where the strands were laid out their entire length with one end of each attached to a "whirl" on the spinning wheel and other ends attached to a single swivel hook called a "loper." A "top" with a separate groove for each strand was placed where the strands came together, while a worker held a handle on "top" and regulated the degree of twist the final product would have. The ends were cut, the strands were worked backward into the strands at each end, and the finished rope was coiled.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, this process was carried out in at least three locations in Henrico County, although no physical evidence of their existence seems to remain. One of these was the Richmond Ropewalk Company, which appears in "A List of Taxable property of Tithes in the 8th Precinct of Henrico County taken by Isaac Younghusband Gent, for the Year 1783." It lists the names of twenty black workers, nineteen of which were Tithes: Ned, Bilberry, Billey, James, Tom, Tabb, Jacob, Collen, Hamilton, Robin, Edmund, Amos, Page, Peter, Frank, Brunswick, Guy, Jonny, Gray, and another Guy. The work was arduous, so it was not suprising to find an advertisement in the 10 May 1783 Virginia Gazette and Weekly Advertiser in which Samuel Coleman, manager of the Richmond Ropewalk Company, offers a reward of ten dollars plus one shilling per mile for the return of a runaway "named Amos, about five ten or eleven inches high, and thirty years of age." Interestingly, it identifies the clothes he arried with him including "two oznabrig shirt," oznabrig being a material made of the same hemp used for ropemaking.

Robert Pleasants, Richard Adams and Robert Mitchell apparently owned the company, and the value of the enterprise is hard to determine. On 11 December 1783, the trio paid Bowles Cook 2500 pounds for a "one twentieth part of said Ropewalk;" while on 20 December 1782 they paid Samuel Sayle and Williams Alexander only 500 pounds for "One share or seventeenth part of the said Ropewalk" (Henrico County Deed Book 1).

While the location of this ropewalk could not be determined, another enterprise involving George Nicolson can be more closely identified. In 1791, Nicolson paid Williams Mayo 160 pounds for a sixteen-acre parcel of land just outside the city, extending back from the James River in the area that is now known as Fulton (Henrico County Deed Book 3, page 630). In fact, there are a number of later newspaper references to lots in "Nicholson's plan" near Port Mayo at Rocketts and Nicholson Street in the area was apparently named for him. (The "h" seems to have been a mistaken insertion after George's departure.) George Nicolson, John Cringan and Wiliams Atcheson were business partners, and he purchased the land on their behalf, while keeping the deed in his name. He managed the business; and in order for him to live near the business, Cringan and Atcheson agreed to the purchase of two and three-quarters of adjacent land in the Rockets area for the dwelling. Nicolson apparently never lived there. Instead, he used it to house the ropewalk's workers, a seemingly common practice for such businesses. Nicolson left for Madeira in 1802, never to return. Nicolson died, and the land was sold to settle his estate. But his former partners had not been compensated for their part of the ownership of the small plot of land. They went to court, and in 1807, the Virginia Supreme Court found in their favor.

Eventually, the land became public property and was offered for sale along with other such "useless State property," as the Daily Dispatch of 6 April 1884 called it. The article went on to say that "The Ropewalk is a steep hillside down on Williamsubrg avenue, diagonally opposite Mr. Jefferson Power's property. Its sole value at present is as a promenade for goats."

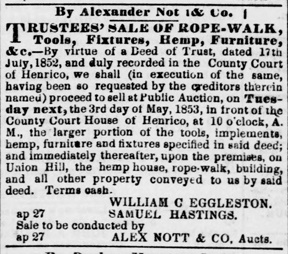

One other ropewalk in the county was on a property on Union Hill. It seems to have been owned by John J. O'Connell. In an 1852 indenture to William Eggleston and Samuel Hastings, he transferred property that included "a Hemp House, Rope walk, stock of hemp, tools, implements, and Rope walk fixtures" and more. With a couple of gaps, the property was bounded by what would eventually become 26th Street, N Street, O Street, and 40th Street. In 1853, Eggleston and Hastings then put the property up for auction (see illustration.) Whether Edward Simons bought it then or not is hard to establish, but he had earlier bought a parcel between 28th, N, 29th, and O Streets, which apparently interrupted the parcel of land that Eggleston and Hastings auctioned. At any rate, Simons operated the ropewalk there, and he seems to have had a rather rough time of it. The 5 February 1858 Richmond Enquirer announced a "Fire in Henrico," and went on to say, "The rope works of Mr. Edward Simons, on Union Hill, was set on fire Wednesday morning about 3 o'clock and burned." It indicated that he lost "about $1,000 worth of hemp, besides a quantity of ready made work and most of his tools." According to the article, this was the second or third time he had experienced a fire, and that he was "a poor man, with a helpless family." Unfortunately, he was uninsured. How much longer the ropewalk remained in operation is not clear, but it did generate a successor elsewhere in Richmond. In the Daily Dispatch of 16 June 1875, Joseph Dowling advertised the opening of a ropewalk; and William E. Simons, son of Edward Simons, included an endorsement of it in the ad.

Ropewalks were by no means rare in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but any remnants or recollections of them are. The sites of these local industrial operations often served as landmarks in articles in area newspapers, indicating the general public's familiarity with them. The familiarity has long since faded, and all we have to mark their existence seems to be one misspelled street in Richmond's east end, Nicholson Street. This industry's local history seems to be at the end of its rope.

Ropewalk locations. Areas highlighted on this 1889 map of Richmond show the likely locations of two ropewalks.

Hyping the hemp. The 7 April 1777 Virginia Gazette offered directions on hemp cultivation and processing to help increase production of this much-needed material.

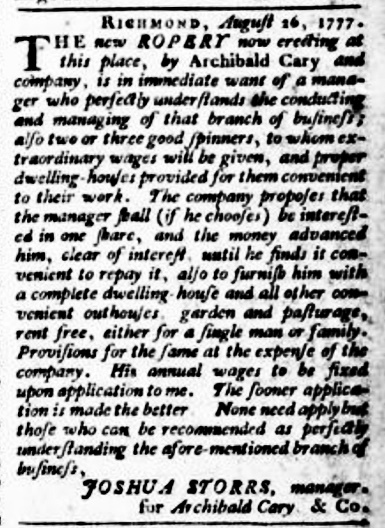

Perks for the manager. The 29 August 1777 Virginia Gazette announces the opening of a new ropery in Richmond. The accommodations offered to the manager and his family indicate the importance of the position as well as the product.

Union Hill ropewalk auctioned. This advertisement from the 2 May 1853 Daily Dispatch describes the elements of the ropewalk that would eventually be operated by Edward Simons.

>Back to Top<

Now You Know

Implement made to easy to get ...Hats off

Maybe we should have included the small picture at the bottom left in the last issue because we had no successful identifiers of the "What Do you Know?" object. Maybe the clue would have helped.

The Chesterfield Hat Corp. apparently supplied this wooden item to help hatters, milliners, and haberdasherers reach hats from shelves in their clothing stores.

Aside from the fedoras sported by urban hipsters and the ubiquitous ball caps often worn backwards, hats are no longer essential elements in the well-dressed man's wardrobe.

Of course, that was not always the case, and the hats that were essential often required specialized implements for their care.

One such item was the hat blocker or stretcher, seen in the picures below. These items helped maintain a hat's shape, could reshape one that had become misshapen or could stretch the hat if ncessary.

The two small images below are views of the same blocker - one open and one closed. As the central handle on the closed stretcher seen at the top was turned, the stretcher's diameter progressively enlarged, as seen in the second image. This would stretch the hat. It could also be used to maintain the hat's shape, much like shoe trees do to shoes.

The larger stretcher on the stand below is an elegant Victorian model which expanded as the handle was turned.

>Back to Top<

What Do You Know?

The porcelain object with the perforations in the top seen left is just over 5" tall.

Do you know what it is?

Email your answers to: jboehling@verizon.net

If you have an unusual object that you thnk we might be interested in for this quarterly feature, let us know. We'd love to hear from you!

>Back to Top<

News 2019: Third Quarter

First Quarter | Second Quarter | Fourth Quarter

Home | Henrico | Maps | Genealogy | Preservation | Membership | Shopping | HCHS

|